Understanding Lightning Part III – Two-Way Channels

This is the third part of a four-part series about the Lightning Network. See parts I, II, and IV.

In the last post of this series we discussed the concept of a one-way payment channel, where Alice can pay Bob, but Bob cannot pay Alice.

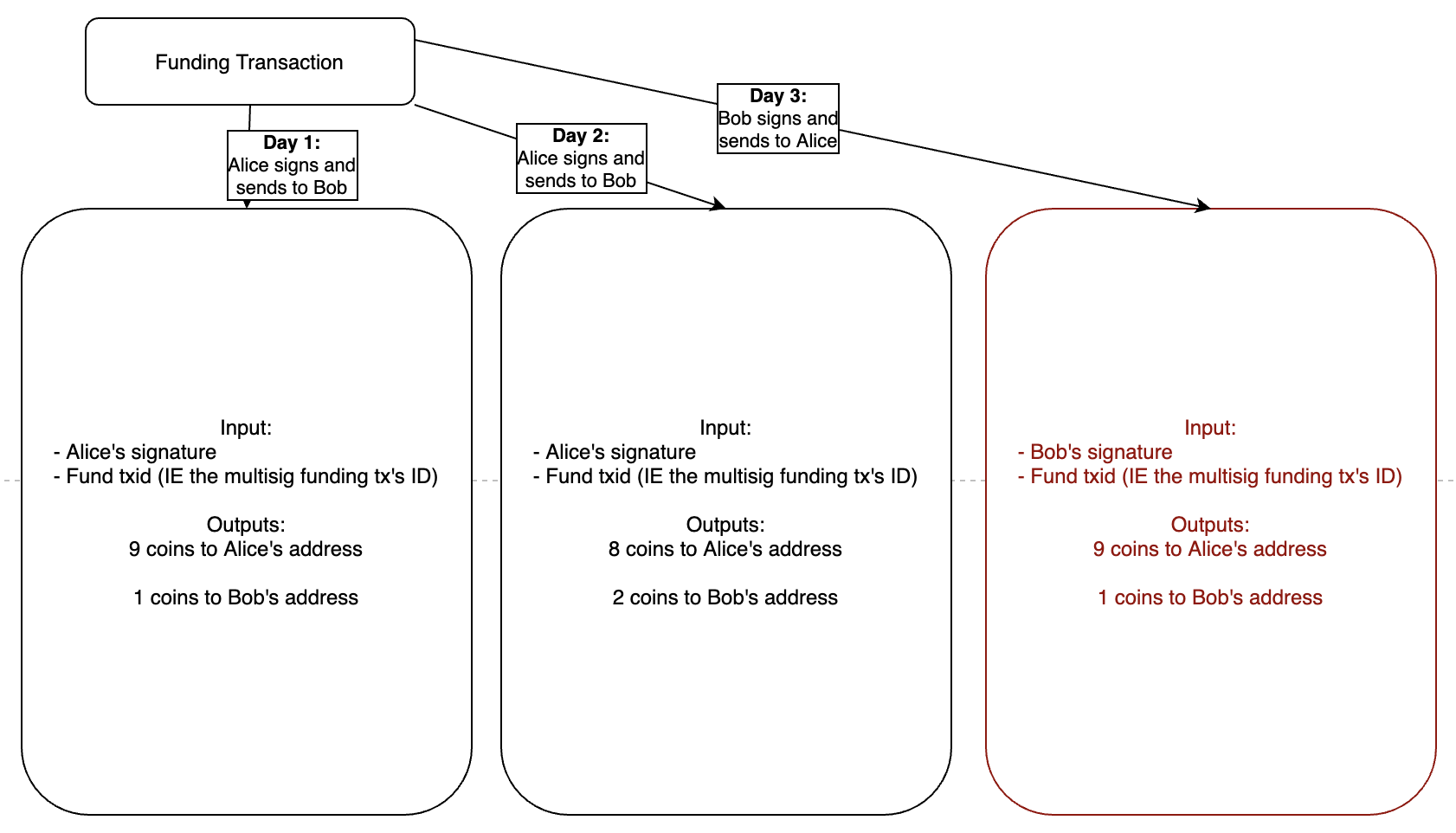

Looking at this image:

We can see that the reason that the previous payment channel won’t work in two directions is that Bob has no credible way to prove to Alice that he won’t just broadcast an earlier transaction that is more favorable for him.

What we really need for the payment channel to work in both directions (Alice pays Bob, Bob pays Alice) is a way for Bob to revoke prior transactions so that Alice knows that he can’t use them, and vice versa.

In this post, we’re going to walk through a payment channel structure that lets Bob and Alice pay one another, and revoke any prior transactions in the payment channel as they go. This is called a bi-directional or two-way payment channel.

Funding a Two-Way Payment Channel

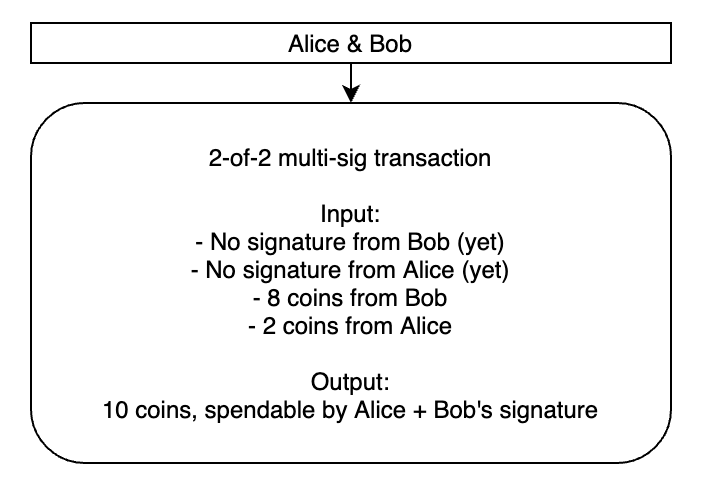

Let’s take a look at how Alice and Bob can fund this payment channel:

Here we have the initial funding transaction. This looks similar to the funding transaction from the previous post where we examined one-way payment channels. Two key differences are that 1. There is no timelock on this transaction (IE it will never expire), and 2. This transaction is not signed yet, meaning that it cannot be broadcasted yet.

The reason that we have no timelock on this transaction is that, as we’ll see in just a moment, any party will be able to close the channel at any time. Recall that we used a timelock previously to prevent a situation where Bob refuses to cooperate and Alice’s coins are stuck in the funding transaction. In this implementation of a payment channel, such a situation can be avoided completely without any kind of expiration date on the channel.

Here’s how we can avoid a non-cooperation frozen funds scenario: Notice that, at the moment, the funding transaction cannot be broadcasted to the blockchain because of the missing signatures. Alice and Bob left their signatures off of the transaction purposefully, because they both want to ensure that they’ll have a way to get their coins back in the event of non-cooperation. Since we have no timelock, neither party currently has a guarantee about being able to get their money back.

The way that Alice and Bob can give each other a guarantee, before opening the payment channel, is to exchange refund transactions before signing and broadcasting the funding transaction.

Exchanging Refund Transactions

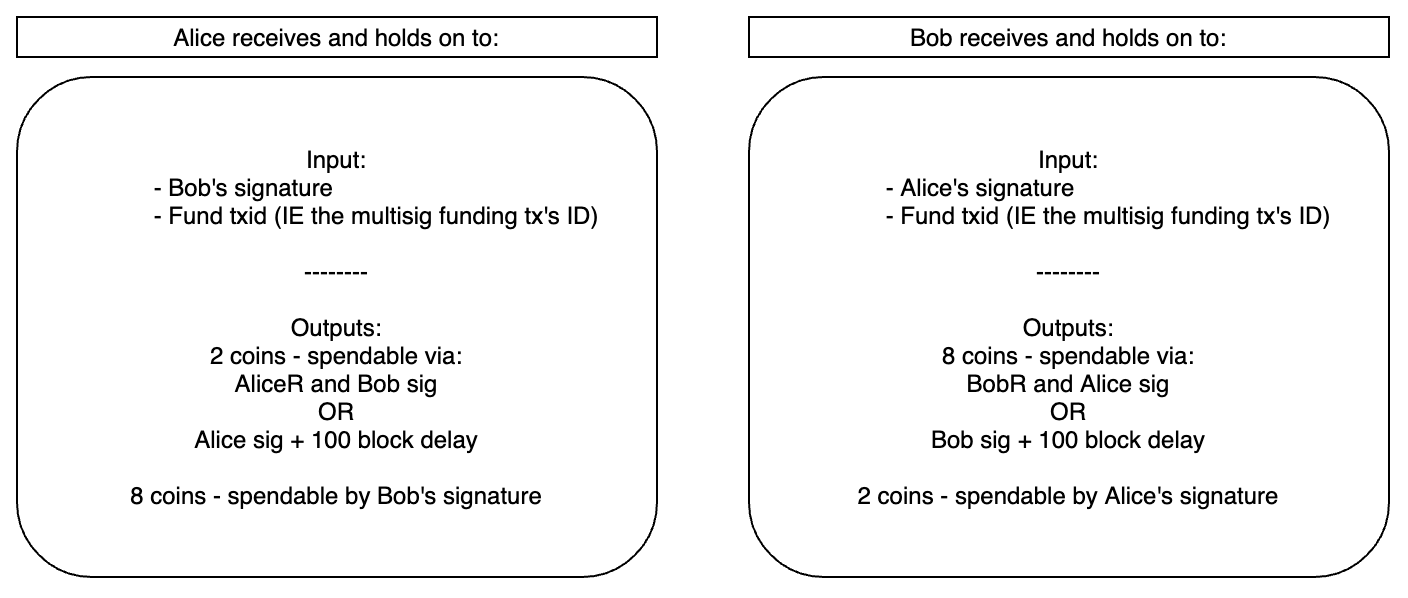

Before Alice and Bob can safely open the payment channel, they will exchange the following refund transactions:

These transactions are based on the funding transaction. But since this a funding transaction cannot be broadcasted yet, these transactions are not yet able to be broadcasted either. They would be rejected by any Bitcoin node that receives them, because they are trying to spend coins from a transaction that isn’t in the blockchain yet.

While these transactions aren’t valid yet, they do give Alice and Bob each the certainty that either one will be able to close the payment channel unilaterally if the two aren’t able to cooperate. Here’s how it works from Alice’s perspective:

- Alice receives this refund transaction, with Bob’s signature

- Alice and Bob sign the funding transaction, then broadcast it to the Bitcoin blockchain

- Once the funding transaction is in the Bitcoin blockchain, Alice could sign and broadcast this refund transaction at any time (because it already has Bob’s signature on it, it just needs hers in order to become valid).

But what about the conditions on the output of this transaction? In Alice’s case, the output looks like this:

2 coins - spendable via:

- AliceR + Bob's signature, OR

- Alice's signature + 100 block delay

8 coins - spendable by Bob's signature

The logic for the 8-coin output is straightforward - if Alice broadcasts this refund transaction, Bob gets his 8 coins back immediately and can spend them whenever he wants.

For Alice, however, she can spend her 2-coin output using one of two conditions:

- If she has some key,

AliceR, and she has Bob’s signature, she can spend the coins immediately - Otherwise, she can spend the coins on her own, but not until this transaction is 100 blocks old

For now, go ahead and ignore the first condition and just think about the second. Alice can get her coins back at any time, but they are encumbered for 100 blocks.

There’s a subtle distinction here about transactions vs. outputs. Alice can broadcast the refund transaction at any time after the payment channel has been opened, and that refund transaction will be valid and accepted by other Bitcoin nodes, but she cannot spend the output from that transaction, using her signature alone, until 100 blocks have passed from the block where the transaction was included.

So we’ve shown that Alice and Bob can give each other refund transactions before opening a payment channel. But why do those transactions have such odd output conditions? What’s with the AliceR and BobR conditions? And why a 100 block delay?

Those unintuitive conditions are what will allow Alice and Bob to revoke transactions, which we’ll cover next.

Revoking the Refund Transactions

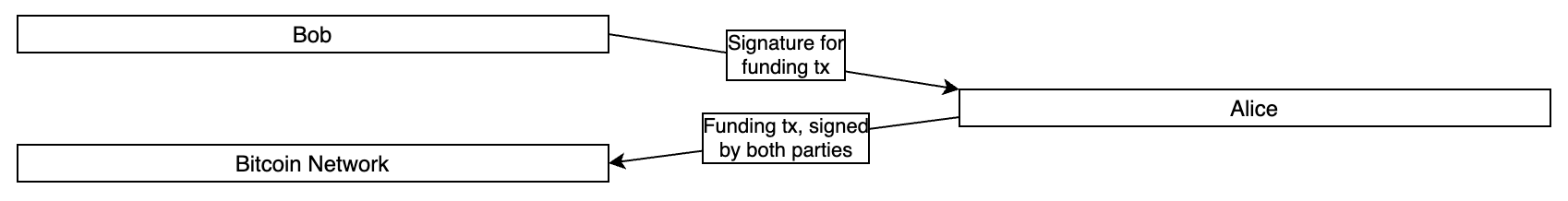

Once Alice and Bob have exchanged refund transactions, they can sign and broadcast the funding transaction:

Which will open the the payment channel. At this point, the payment channel is open, and both Bob and Alice have the ability, using the refund transactions, to close the channel unilaterally at any time.

But, since Bob and Alice each already have a valid transaction that they can broadcast, there’s a problem. Alice can claim 2 coins and Bob can claim 8 using the refund transaction. If Alice then sends Bob 1 coin (making his new balance 9 and hers 1), Bob knows that Alice could still broadcast her refund transaction, claiming 2 coins. Given that the refund transactions allow either party to claim their initial funds at any time, it would seem that this payment channel can never be updated!

This is where those odd output conditions come into play. Alice and Bob can use these conditions to revoke the refund transactions, which in this case just means credibly promising not to try and broadcast the transaction.

Recall the two possible spending conditions for Alice’s refund transaction:

- If she has some key,

AliceR, and she has Bob’s signature, she can spend the coins immediately - Otherwise, she can spend the coins on her own, but not until this transaction is 100 blocks old

Alice created the AliceR key when she and Bob created the refund transactions - it’s just a one-time secret. She knows this key, but Bob doesn’t. So by default, Bob cannot spend Alice’s 2 coins from her refund transaction. But what if Alice gave Bob the AliceR key? If Bob has the AliceR key, and Alice signs and broadcasts her refund transaction, Bob can steal Alice’s coins! He can do this because he can spend right away, using his signature and the AliceR key, while Alice has to wait 100 blocks. So as long as he gets his transaction included in the blockchain before the 100 blocks are up, the money is his.

So we can see that for Alice and Bob to revoke their refund transactions, it’s as simple as sending each other a key; AliceR allows Alice to revoke her refund transaction, and BobR lets Bob revoke his refund transaction.

Sending Money in a Two-Way Payment Channel

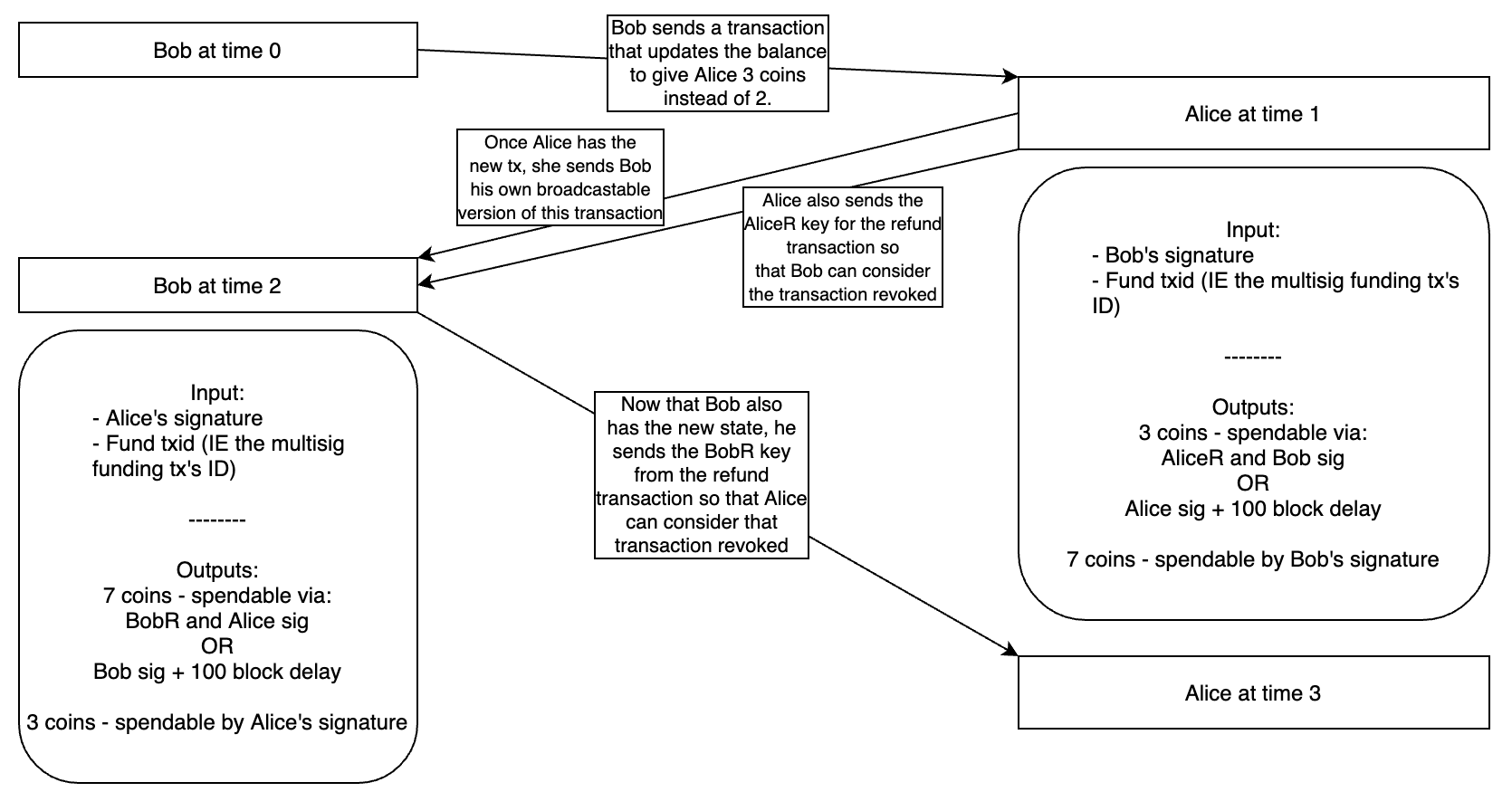

Using the revocation scheme described above, Bob can send Alice money like so:

Here’s what’s happening at each step of the process:

- Bob sends Alice a new transaction, that gives her

1coin, so that her new balance is3and his is7. At this point, Alice can broadcast this new transaction, or she can broadcast her refund transaction. Bob can also broadcast his refund transaction. - Now that Alice has the new transaction, she does two things:

- She sends Bob his own version of the new transaction, that has her signature. This is the exact same idea as exchanging refund transactions, so that each party always has a valid transaction that they could broadcast to close the channel.

- She sends Bob the

AliceRkey for her refund transaction. After sending these two messages to Bob, Alice can broadcast the new transaction, but she can’t broadcast her refund transaction because Bob could steal the coins from that transaction using theAliceRkey. Bob can broadcast the new transaction or he can broadcast his refund transaction.

- To complete the transaction, Bob sends Alice the

BobRkey for his refund transaction. After doing this, both Bob and Alice are able to broadcast the new state, where Alice has3coins and Bob has7. But neither party can broadcast the refund transactions because doing so would allow the other to steal their coins.

By doing revocation in this way, Alice and Bob can keep the payment channel open forever, sending each other arbitrary amounts of money as long as neither’s balance goes negative.

As you can see, revoking transactions provides Alice and Bob with a way to send each other money using a two-way payment channel. There’s a little problem though - for Alice and Bob to transact, they must open a payment channel on the Bitcoin blockchain. But if Bitcoin fees grow over time, it won’t be feasible for Alice to open a payment channel with every single merchant that she uses. What if there were a way for Alice and Bob to pay each other without having a payment channel between the two of them? We’ll examine how that works in the final post of this series.